Is there room for a new political party in Turkey?

Since 2015, patterns in voting behavior have been shifting. Poor governance and a stagnant economy are largely behind this change.

Changes in voting behavior occur through two main mechanisms. The first mechanism is caused by a shock to the system. In Turkey's recent history, a notable example came with the 2001 banking crisis as age-old political parties and leaders were wiped out to be replaced by the Justice and Development party (AK Party).

The second mechanism is a process that happens over time and takes long to manifest itself.

Since 2015, such a process has been taking place in Turkey. Growing disenchantment over poor governance and a stagnant economy has began to upend seemingly unchanging patterns in voting behavior. In the June 2015 general elections, the AK Party managed to come first. But in an unprecedented manner since its ascent to power, it failed to secure a parliamentary majority.

The passing of a 10% of votes threshold in Turkey's parliament by the pro-Kurdish People's Democratic party (HDP) was partly responsible for this. Yet of equal importance was the pre-eminence of economic concerns in campaign debates. Most notably, a promise made by the opposition Republican People's party (CHP) to raise the minimum wage.

Fast forwarding to the referendum over constitutional change of April 2017, while the resulting vote endorsed the change, the victory of was a slim one, with a meager 51.41% of the electorate in favor and 48,59% against. A breakdown of the electoral results highlighted an emerging pattern. In many large cities including Ankara and Istanbul the vote was negative.

The cities that voted against the change were the ones embedded in metropolitan economies and highly connected to the outside world, either through trade or tourism. Moreover, the referendum results coincided with with mounting popular support for Turkey's EU membership, rising from 42-44% to 52-55%. A recent poll conducted in September by Istanbul Economics Research revealed that 52% of the Turkish population now supports Turkey’s EU membership.

Such shifting voting patterns surfaced more strikingly in the local elections of March 31 and during the re-run of the election in Istanbul on June 23. The AK Party lost control over 6 large Turkish cities - and thus of 65% of GDP - to the opposition block that had rallied behind CHP candidates.

The first cause of this was a significant fall in disposable income. In the wake of Turkey's currency crisis in the summer of 2018, inflation surged, affecting food prices in particular. Meanwhile, unemployment stood at a stubborn 14%.

Another factor behind this shift was the opposition's newfound ability to nominate candidates that could reach out to voters on all sides of the political spectrum. As a result, Turkey's large urban centers vigorously reacted to the incumbent administration. The municipal elections were the outcome of a process that had long been in the making.

Turkey has swing voters

Another significant development that came about with the municipal elections was the emergence of a group of swing voters within the Turkish electorate. Turkish politics had not seen such a camp for the past 15 years. Whilst sticking to the same ideological camp, a part of the electorate chose to vote for alternative parties. Back in June 2018, some dissatisfied AKP voters switched their allegiance for the MHP, remaining within the "People's Alliance" (Cumhur İttifakı) between the AK Party and the MHP. Our research shows that 13-15% of the electorate, predominantly AK Party voters, are likely to vote outside of the "People's Alliance" if a viable alternative was introduced. Yet in the absence of such an alternative, those voters opt to abide by the Alliance.

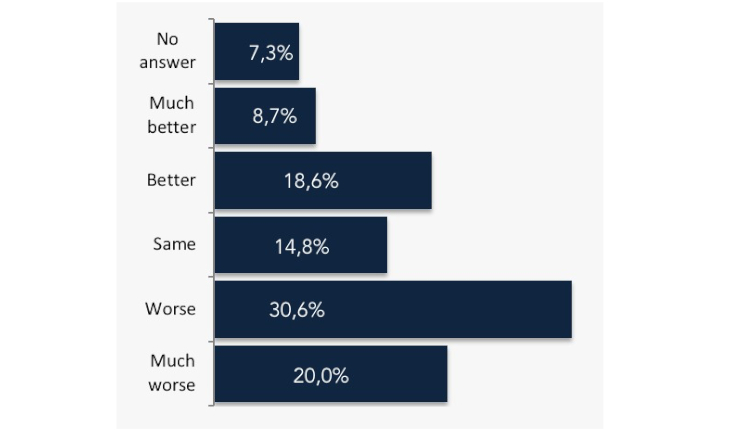

Still, it appears the sentiment regarding Erdoğan's newly established presidential system is turning sour. According to a poll funded and conducted by Istanbul Economic Research in September 2019 with 1537 people in 12 Turkish cities, 50% of people reported they believed Turkey fared "worse" or "much worse" under the new presidential system.

Under the new presidential system, Turkey fares:

In sum, these data and the general shift in voting behavior patterns strongly suggest there is room for new parties in Turkey's political landscape. That applies especially to the center-right of the political spectrum. In that light, the discussions regarding the possible foundation of two new parties by former AK Party figures Ali Babacan and Ahmet Davutoğlu come as no surprise. Despite the country's political polarization, the struggle for control of Turkish politics will largely be a fight for the center.