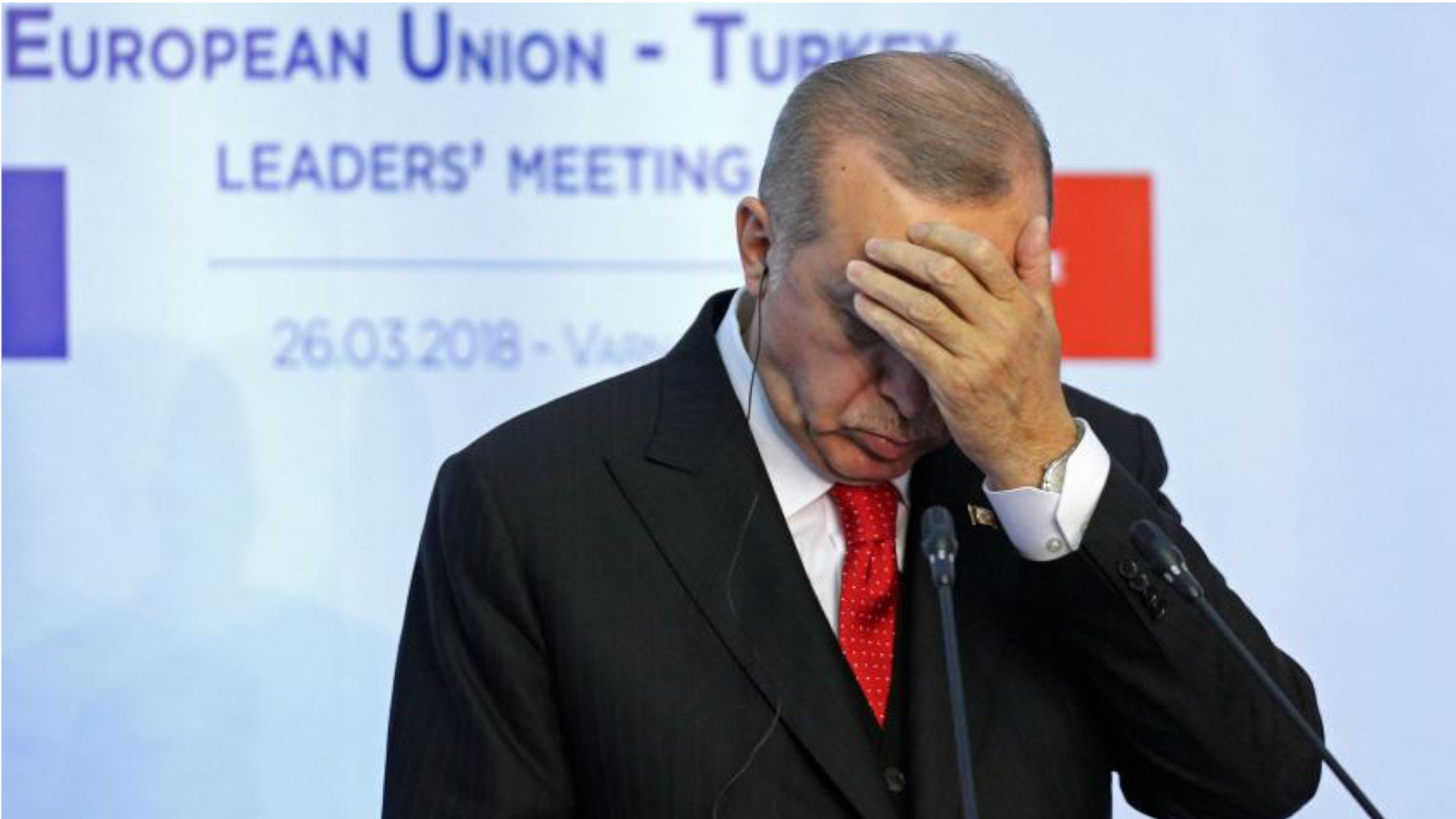

'EU wants to tame Turkey’s foreign policy'

According to Sinem Adar, a researcher at the Center for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), Brussels and Washington will continue to exert pressure on Ankara to tame its foreign policy until the next EU summit in June. "It seems likely that it will be the U.S. - not the EU - that will focus on human rights issues, Adar argued.

Ayşegül Karakülhancı/ Cologne

At the EU Council Summit of March 25-26, leaders agreed on a 11-point statement, which emphasized the necessity of cooperation and dialogue with Turkey whilst maintaining that the prospect of sanctions was still on the agenda.

In December 2020, EU leaders gave Turkey some time until the March summit with regards to potential sanctions. This time around, pushed by the Biden administration, they postponed key decisions until another summit to held in June. It is now clear that the EU and the U.S. will continue to exert pressure on Turkey and expect it to undertake several steps, especially in the realm of foreign policy. We spoke to Sinem Adar, a researcher at the Center for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), about what the EU’s latest summit results entail for Turkey, the reasons and consequences of Ankara’s recent foreign policy decisions and how the EU’s policy towards Turkey may evolve in the future.

Q: How do you evaluate the decisions of the European Union’s summit on Turkey in terms of Turkey-EU relations?

A: It largely coincides with decisions made at summits in both October and December last year. Although not explicitly stated at the October 2020 summit, the EU took a step towards separating the modernization of the Customs Union from the framework of the accession talks. It stipulated the modernization of the Customs Union with steps Turkey would undertake in the Eastern Mediterranean. This same stance was upheld in December. The decisions of March 25-26 are in line with the October and December summits, but the EU is signaling to Ankara that it is pursuing a “wait and see” approach. In other words, while expressing satisfaction that Turkey has taken a step back in the Eastern Mediterranean, it nevertheless sends the message that they are open to cooperation, especially in the economic sphere, in the event Turkey maintains its agreeable attitude on the Eastern Mediterranean and Cyprus issues. In the event Turkey does not, it has been stated that the EU will not hesitate to use the instruments and options at its disposal to guard its interests. Of course, at this point, the report prepared by Joseph Borrell, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, regarding Turkey, is noteworthy.

The scale of the EU instruments to be used for Turkey has been expanded to include sanctions. The list includes provisions such as narrowing the areas of economic co-operation between the EU and Turkey, restricting the activities of the EU Investment Bank and other financial institutions. There are also measures targeting sectors important to Turkish economy, such as tourism and possible import and export bans on the energy sector. As Turkey finds itself in a grave economic crisis, the EU is using economic pressure again Ankara to tame its foreign policy. Of course, it should be noted that the decisions of the summit emphasize that the financial support for refugees will continue and that they want to continue to work with Turkey on border control and refugee readmission.

Q: Turkey’s opposition has criticized the EU for not taking drastic steps. However, the fact that new chapters have not been opened, the termination of accession talks and the suspension of the renewal of the Customs Union effectively served as coercion tools against Turkey. Moreover, the EU already raised the prospect of sanctions against certain individuals and economic sectors. What more can the EU do? Does the EU have any more instruments left?

A: Democratic actors in Turkey accuse the EU of not taking a stronger critical position with regards to human rights, increasing suppression and disregard of the rule of law. In a sense, they are right because, at the October 2020 summit, the EU made a choice to separate the framework of membership talks that directly concern both human rights and the rule of law from the modernization of the Customs Union. Also, conditionality in relations was indexed to foreign policy. But accession talks were practically nonfunctional since 2016 and Turkey’s foreign policy relies on the use of force, which is not in line with the principles of international law.

Regarding the extent of this path and possible other instruments, last week’s decisions actually point out to stronger steps in increasing economic pressure on Turkey. The question to be asked may be the following: Are there any normative means of pressure left in a situation in which the accession talks are not functioning? The human rights sanctions regime that was adopted in 2020 could be used. Even though Turkey’s negotiation process is frozen, I don’t know how much room for maneuver there is technically and legally to use these sanctions, as it is still a member state of the EU.

Q: In the EU statement, the expression “neighboring country” is used to emphasize Turkey’s geo-political position and strategic importance whilst carefully the expression “candidate country” is carefully avoided. In this statement, there is no mention of Turkey’s candidacy to join the EU. It does not seem to attract any attention either. Would it be right to interpret it that way?

A: I agree, the whole process is evolving into that. There have always been ups and downs in EU-Turkey relations. This is one of the downs, but unlike other similar periods, it does not seem easy to overcome this. The trajectory is to completely marginalize the framework of the membership talks, which is not a process that started yesterday. In fact, it has been going on since 2013.

Steps such as the EU presenting Turkey with a roadmap for visa liberalization in 2013, and then signing the refugee readmission deal in 2013, were conducted outside the technical framework of the accession talks. Likewise, a very important point in this process is the cooperation conducted concerning refugees in November 2015 and March 2016. However, although a relationship and a form of relating, in parallel with the framework of the accession talks, have been developing since 2013, there was still an emphasis on human rights and the norms of the rule of law in this process, even though one can argue regarding the decreasing tone. As of the October 2020 summit, it is safe to say that democratic conditionality has no effect left in practice, if not formally. Security and economic co-operation with Turkey has replaced the human rights and democracy-based relationship. It seems likely that with Joe Biden winning the election, it will be the U.S. - not the EU - that will focus on human rights issues.

Q: So, it seems like it will mostly be the US that will be concerned with Turkey’s domestic affairs, and not the EU.

A: The data we have so far suggests that such a situation is possible. Until very recently, the United States was the actor who put pressure on the EU for Turkey to become a member state. Today, we can say that the United States bids to play a more active role with regards to democracy and human rights.

Q: Immediately after meeting with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen on March 19 before the EU summit, Ankara announced that it was withdrawing from the Istanbul Convention. Turkey is taking such drastic steps and it is so far from conciliation that at this point, how can the EU conduct a policy with Turkey based on human rights and democracy? What instruments does it have aside from the economy? And why would the EU bother with Turkey’s democratization process?

A: Aside from the economy, the EU does not have many tools to urge Turkey’s regime to change its behavior. They seem to have decided to use it primarily for a change of behavior in foreign policy. However, they could still cut off funds transferred entirely within the framework of EU accession negotiations, which already have gone through a significant reduction. They could also use the human rights sanctions package they adopted last year for Turkey. Erasmus programs between Turkey and the EU could be cancelled. But I also think it is necessary to ask the question of who is being punished when you do these things. If the goal here is to change the behavior of the ruling bloc that governs Turkey, will these tools lead to a change in behavior? I don’t think that’s an easy question to answer. However, an arms embargo and restrictions on exports as well as sanctions against individuals can be effective. Of course, there is the discourse dimension. A symbolic stance that goes one step further than a denouncement could further spur the growing belief amongst Turkey’s democratic actors that the UE is no longer an institution based on democratic principles and norms.

A democratic Turkey is not only an issue of principles for the EU, but also a matter of interest. Stability can be considered more important in interrelations of states than democratic norms. However, we are able to observe that the authoritarian regime cannot be stabilized due to Turkey’s unique economic, political and social conditions.

Q: How should we evaluate US President Joe Biden's participation in the EU summit focusing on Turkey while he has not had a direct contact with Ankara?

A: With Biden’s election as president, political actors in several member states have sent messages that the EU is ready and willing to restore US-Transatlantic relations under Biden. Of course, the possibility of the EU and the US working together again is of direct interest to Turkey. Likewise, many experts commented that the EU postponed radical decisions until March to buy time to see what the Biden administration would do. A new period of cooperation in transatlantic relations and NATO generally has started between the Biden administration and the EU. This is not specific to Turkey. Biden’s attendance could be interpreted as both a goodwill message from the US to the EU as well as a message to Turkey and Russia.

Q: Germany will hold general elections in September this year. Merkel will no longer be the prime minister. There are French elections in 2022. Macron expressed concern about Turkey’s interference in the elections. Maybe there is a similar kind of anxiety in Germany. How would you evaluate this statement? Does Turkey really have such power?

A: When we compare Macron’s outbursts and discourse regarding both Erdoğan and Turkey with Merkel’s rhetoric, we see a significant difference. Macron likes to speak with a high pitch and make statements that can sometimes be considered provocative. In this context, he is not afraid to use strong language regarding Turkey also due to the influence of French domestic politics. It is different in Germany. The Germans refrain from engaging in a row with Turkey’s political actors. I think this is a conscious choice. The situation here has certain dynamics of domestic politics as well as personal differences of politicians. However, there is also a perception within the EU since 2016 that Turkey is a problematic actor both in EU relations, in its relations with NATO and in the context of its activities in the Middle East and North Africa, which is called the southern quarter of the EU. This is so even in the eyes of member states that have historically been more moderate towards Turkey. Take Germany. Although it is a country that has been moderate towards Turkey for economic and sociopolitical reasons, there has been a change in its perception of Turkey within the past two years.

Turkey has obviously reached its limits on its mainly force-based foreign policy it has been conducting since 2016; after Biden won the U.S. elections and when the economic crisis in Turkey worsened. Within the past five years, both bilateral relations and relations with supra-state organizations such as NATO and the EU have been severely damaged. In fact, I think that the defiant and unpredictable swings in its foreign policy have a direct relationship with this damage.

Q: In fact, both the opposition and the government occasionally accuse the EU of hypocrisy. What do you think, is the EU a hypocrite?

A: After all, the EU behaves the way a state behaves. In other words, it is trying to operate without damaging relations with Turkey’s current government and without harming the interests of the union as a whole and its member states, or with the least degree of damage. What contrasts or confuses us here is that those steps taken for the sake of interests do not match with the normative stance of an institution that has a claim to democratic norms and principles. The most important reason for this is that Turkey is still officially a member state. For instance, there is far less criticism against the EU for working with authoritarian regimes that are far from democratic procedures, such as Egypt or Saudi Arabia. However, one point that should be underlined is the issue that cooperation with authoritarian states by putting interests before democratic principles can intentionally or unknowingly prolong the life of these states or prop up their legitimacy. One of the best examples of this is the migration cooperation between Turkey and the EU in November 2015 and March 2016, while an active conflict took place in the Kurdish provinces and districts of Southern and Eastern Anatolia. Turkey’s authoritarianism is not a process that began in 2018.

Q: How could relations with Turkey proceed after Germany’s EU presidency is over?

A: Among member states, Germany considers Turkey to be a market with a high capacity. In addition, relations with Turkey are a matter of domestic politics for Germany, as Europe’s largest Turkish diaspora resides in Germany. France, on the other hand, sees Turkey as a strategic rival, especially in its foreign policy. Likewise, one of the main reasons why France is very strongly critical of Turkey from the mid-2020 is that Turkey is involved in the Libyan war. The EU presidency will move to France in 2022. It may not be an easy period for Turkey.

Q: The government in Turkey prefers to strengthen its rule with consecutive crises as a method. It has been doing the same in foreign policy also for a long time. But now it has started negotiations with Greece, backed down in Libya, etc. Is there no other step left for Turkey to take in foreign policy? Will Ankara’s foreign policy now take a more definite, more coherent path?

A: Since 2016, Turkey's rulers have responded to criticism of the increasingly militaristic foreign policy with the argument that “Turkey has opted for this to make room for itself at the table.” Both the November 2020 U.S. election results and the deepening economic crisis are two important factors that seriously restrict Turkey in the conduct of its foreign policy. We are facing a foreign policy that has reached its limits. Ankara is somewhat backing down in its foreign policy not because of preferences but because of necessities. The wearing off of state institutions, the elimination of the separation of powers and the erosion of the principle of merit have seriously damaged Turkey’s diplomatic and political abilities and capabilities in the past five years, and it is not so easy to repair the damage.

It stands out that it is not so easy when there is a lack of responses to the steps taken in countries such as Egypt and Israel to repair deteriorating relations. It has been four months since the Biden administration came to power, and there has not been any presidential-level communication yet. The Biden administration released its national security strategy report in early March. Immediately after that, Blinken, the U.S. Secretary of State, announced his foreign policy vision. Combatting autocratic regimes has been determined as a part of the new national security strategy in both of them. This can be interpreted as a variable that increases Turkey’s foreign policy requirements. Likewise, the EU’s efforts to tame Turkey through economic engagements and pressure. Therefore, the steps Turkey has taken back in its foreign policy are a necessary and tactical move.

Germany calls for closer EU-Turkey cooperationDiplomacy

Germany calls for closer EU-Turkey cooperationDiplomacy Turkish foreign policy: Any need to be anti-Western?Diplomacy

Turkish foreign policy: Any need to be anti-Western?Diplomacy Living on borrowed timeWorld

Living on borrowed timeWorld