Why Istanbul must be an eco-feminist city

Merve Tuba Tanok writes: The reasons for reclaiming a management approach based on ecological and feminist perspectives for the urban and semi-rural areas of Istanbul, a city with a complex structure and a population of 20 million that could almost be a country itself, are both local and regional as well as global.

Merve Tuba Tanok

The reasons for reclaiming a management approach based on ecological and feminist perspectives for the urban and semi-rural areas of Istanbul, a city with a complex structure and a population of 20 million that could almost be a country itself, are both local and regional as well as global.

The current situation in the city — the environmentally critical and unprecedented nature of which has been exposed through the epidemic — necessitates a vitally urgent, nature-centered form of management when it comes to the conservation and recovery of the environment. While some countries are seeing a flurry of tree planting, Turkey, as a country that systemically massacres its forests, has shown that it is in the wrong position when it comes to protecting the global ecosystem.

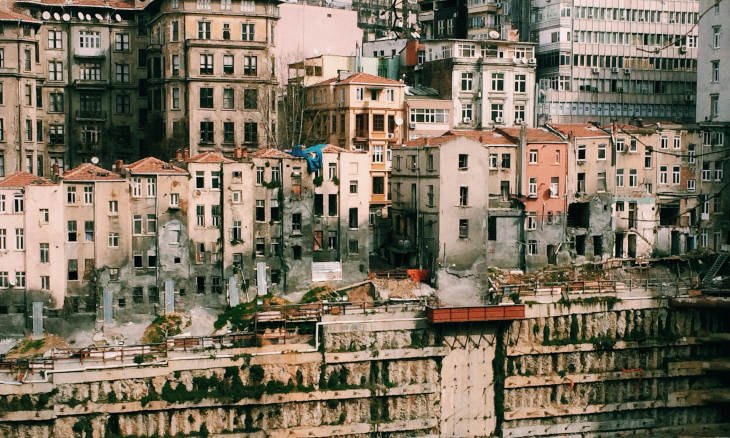

Undoubtedly, Istanbul has an important place in the recovery of this ecological destruction. Beyond the economic and political dynamics of the third Bosphorus bridge, the third airport and the Kanal Istanbul project, we can say that the choice of location for these projects alone is already a cause for a death warrant for Istanbul’s natural and urban life. These construction projects, which have annihilated hectares of forest, and the planned future projects as well, indicate that this ecological destruction will soon affect potable water for the city as well as the air we breathe. This is due to the crucial selection of the north of the city, which is home to the city’s last remaining nature and water reserves, for the location of the projects. The subordination and exploitation of nature that has occurred throughout the past centuries as well as today is performed through a masculine understanding that is concentrated around a helix of power and domination. The ruling class, in the pursuit of wealth accumulation, sees no harm in the pillage of nature, as it is a capitalist tradition. More power, more velocity, more exploitation, and more destruction — what a Faustian reality.

The reason for such spatial structures today are based on similar parameters of power, namely the masculine construction of space. This construction forms Istanbul through a phallic urban identity and creates urban projects that neglect ecology. They are systematically reproduced by guaranteeing the continuation of increasingly deepening socio-spatial inequality, starting with the Büyükdere line. This type of spatial structure is also the reason why women walk the streets in fear, and why they and their children cannot feel safe.

The murder of women as well as harassment and rape cases are rising dramatically, and while the reason for those acts are male desire and the systematic male-power dominance, women are held responsible for that male violence. Nature and women are subjugated synchronously, so without waiting for the slaughter of more women and more forests, one of the most important issues that urban management should take action in defense of is nature and women. This is just as crucial as taking measures against the epidemic, and it is one of the key issues in the context of the production of counter-hegemonic space and life. Not neglecting the influence of the urban environment on the creation process of those problems is quite essential for the sake of a peaceful and non-conflictive habitat. For that very reason, strategies of feminist and even eco-feminist production of space that firstly provide for the security of women and enable the right to the city and a sustainable habitat for every segment of society must come to prominence in the production of spatial and socio-economic strategies by urban management. Including feminist political ecology in city management is key for the rescue of our everyday life, since it involves not only women, but all people who are oppressed and excluded in the city.

Ecofeminist cooperatives will be a key element of an ecofeminist city. They must be provided by either urban management or organized horizontally, and should be considered to be a vital alternative for women’s economic independence, which is a key step for women’s liberation. For example, instead of waiting for the “great Istanbul earthquake,” as the closest natural disaster we are aware of, ecofeminist cooperatives can work on post-earthquake housing based on use of natural and accessible material — thus excluding construction monopolies — as soon as the epidemic period is over. The walling materials could be produced by a district’s ecofeminist cooperative, for instance, and could reject architectural dullness and the politicialness of social housing. Such housing would be designed and decided by participative processes that are women-, children- and elder-centered, non-discriminatory and ecological. Of course, without waiting for the administrative level, something should be done through collective production and individual awareness in order to avoid having this period turn into the end times.

Perhaps the only positive situation the quarantine period has given us is the chance to discover our own practices of self-sufficiency. Self-sufficiency is one of individual and collective steps that can be taken against alienation. That is because moving from an order in which an apple seed is thrown in the garbage to one in which it is planted in the garden is socio-political change.

Author:

Urban and Regional Planner.